Enter the Sensei’s of Rap: How Wu-Tang Definitively Influenced Hip-Hop

Both off the mic and on, the group of nine New Yorkers known as the Wu-Tang Clan would each bring their own different backgrounds, styles and influences to hip-hop culture. Wu-Tang would hit the scene in ‘93 with lyrics about chess, street slang, and marvel comics, all of this while sampling kung-fu flicks. Though these were not common themes in hip-hop at that time, for every reason that the Wu-Tang Clan should not have worked, was another reason that it did. On November 9th, 1993, hip-hop would be changed forever with the release of Wu-Tang’s debut album, Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers).

Before the album’s release, the group’s formation would be as chaotic as you would probably expect from a group of that size. With Ghostface Killah and Raekwon initially starting as street rivals, or RZA and U-God recently leaving incarceration, and members such as Method Man just narrowly escaping death, getting them all into the studio had to be some sort of fate at work. One of the members, RZA, would play a great role in this formation. After being dropped from the label Tommy Boy, he would swear to no longer succumb to the industry’s standards of “hit-making” and would begin producing music that he believed in. The next step in achieving this goal would be bringing together the superpower team to rap over these beats. RZA started in the family, with his cousins, the GZA and Ol’ Dirty Bastard.

The album plays out as a sort of calculated chaos, with no member sounding like another. Though this is the case, they are able to find chemistry through their obvious competitive hunger to deliver the best verse for each track. Whether it was Ghostface Killah’s blunt delivery, Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s sporadic personality or Inspectah Deck’s street knowledge, the groups' varying archetypes were able to find orchestration through the RZA’s guiding direction. While on paper the many topics on the project together could be seen as nonsensical, each members’ ability to bounce energy off one another turns it from just a bunch of ingredients, to a dish. With the Wu-Tang’s choices of themes and styles playing the critical “spices and flavors” that made their “dish” stand out from the rest. It should also be noted that a large percentage of the album’s success should be accounted towards Wu-Tang’s style and branding. With their grimy and low budget music videos, the iconic “W” logo, and chants including the famous, “SUUUU.”

Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) would be an instant hit launching the careers of every member exponentially. Many labels including Def Jam Records would aim to sign the nine piece, but many of them would fail as they wanted to sign the group as solo members along with the group deal. RZA, who played the main role in deal making, would not allow this to happen as he wanted to infect the Wu-Tang brand through the entire industry, not just through one label. The group would eventually sign a group deal with Loud Records, with that solo deal freedom included. Method Man would be first, signing to Def Jam Records.

The Wu-Tang debut album would mark the beginning of Wu-Tang and RZA’s powerful streak of solo and group projects. With Method Man’s catchy Tical, following in 1994. Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s grimy and oddball personality on Return to the 36 Chambers: The Dirty Version, Raekwon’s mafioso movie inspired, Only Built 4 Cuban Linx…, and GZA’s lyrical masterpiece, Liquid Swords in 1995. Ghostface Killah would bring back his back-and-fourths with Raekwon on his debut, Ironman in 1996. Lastly, ending with Wu-Tang’s more mature follow up project Wu-Tang Forever in 1997. A majority of these projects would be almost solely produced by RZA. All of this does not even include the great list of features provided by the members to classic albums including Moment of Truth by Gang Starr, All Eyez on Me by 2Pac and even newer records all the way up to the recent release of Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers by Kendrick Lamar.

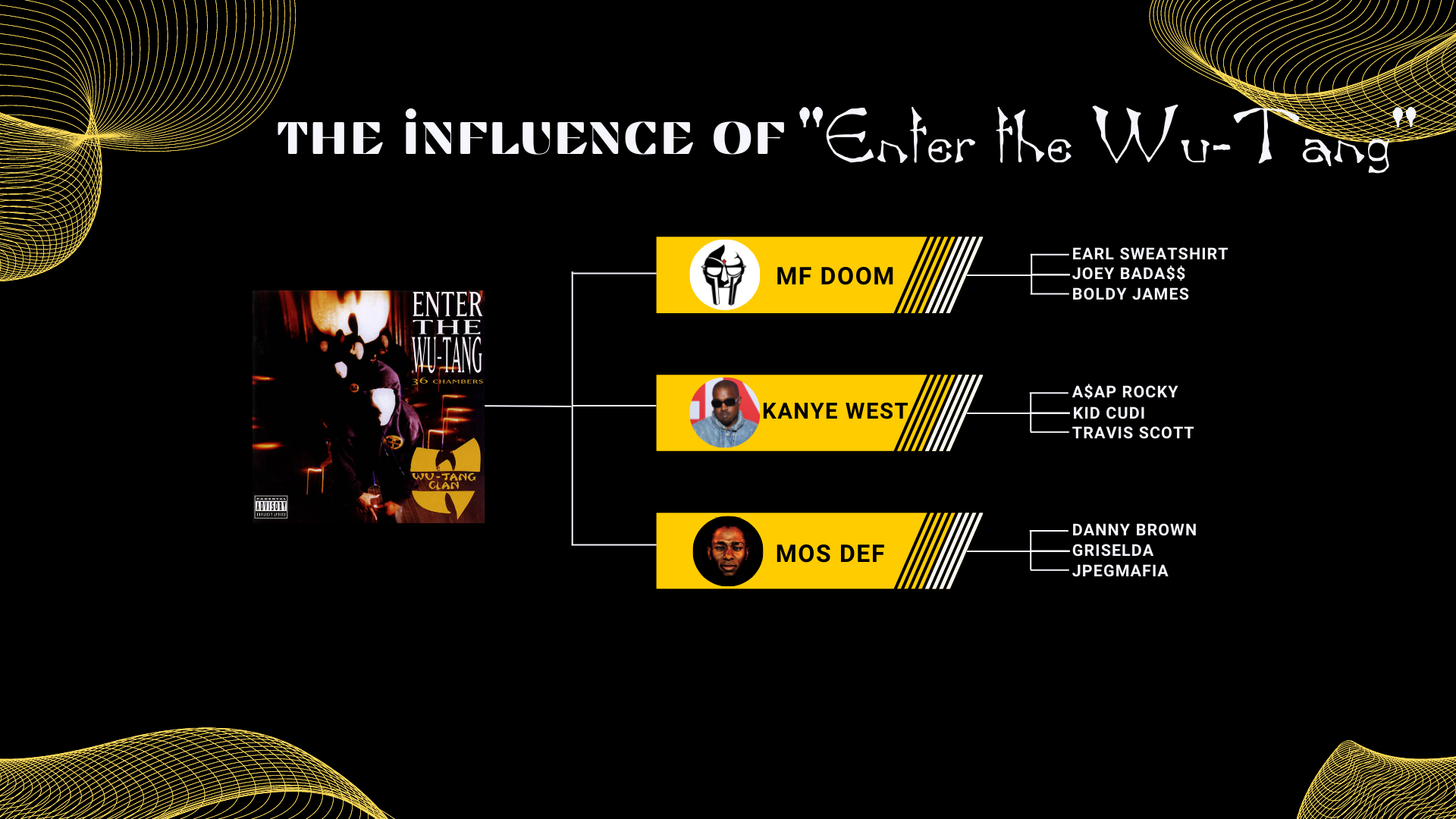

The Wu-Tang debut set the groundwork to inspire generations with each of these projects further creating their own sub-genres and sounds. For example, RZA would be one of the first, if not the first, to adopt the “chipmunk samples” that would become a staple to early Kanye West production. Ghostface Killah would also adopt the persona Tony Starks or “Ironman” which would inspire artists such as MF DOOM or CZARFACE to adopt their own comic book inspired identities. Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s chaotic sound would open the floodgates to many experimental rappers including Mos Def, Danny Brown, JPEGMAFIA and others. Raekwon would help establish mafioso rap in New York and beyond, which would be carried into classic albums like Jay-Z’s, Reasonable Doubt, Notorious B.I.G.‘s, Life After Death and Pusha T’s, DAYTONA. The Wu-Tang Clan were not lying when they said they were for the children, as they would become strong idols and influencers to all kinds of future artists, whether they were from the East or West.

Giovanni Recinos is a staff writer.

Thanks for reading! Follow us on Instagram to stay up-to-date on everything hip-hop.